Introduction

I am honored to have been asked to share a few of my thoughts about the aesthetics embedded in the art of Jorge Soto Sánchez. In this presentation, I will briefly address three basic points. First, he created expressive drawings of fragmented beings using TaÃno like graphological lines and markings. Second, he appropriated images from well-known Puerto Rican paintings and transformed them to express social criticism. Third, he collected found objects to construct painted assemblages representative of personal experiences of the social conditions in which he lived.

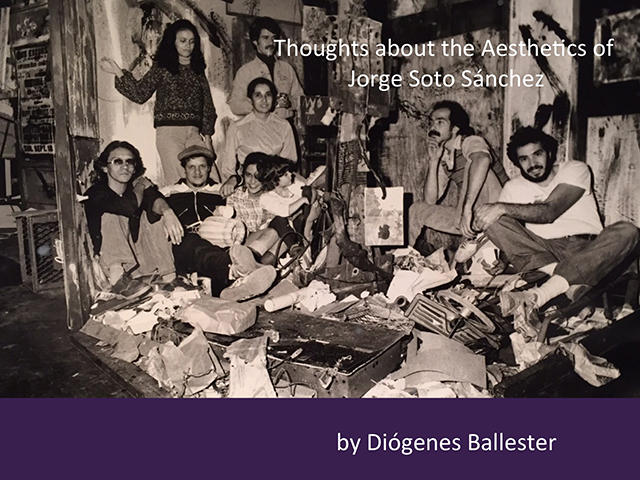

By the late 1960s / early 1970s, Jorge Soto, like other off-spring of post World War II Puerto Rican immigrants to New York City, were searching for identity. Many of their parents had left the island homeland as part of an economically forced migration. They settled in El Barrio, the South Bronx, and the Lower East Side. Their children, first generation immigrants, were racially and culturally alienated from a mainstream society that treated them as other than and in which they occupied the lower strata of the working class. They looked to their experiences in los barrios and their roots in Puerto Rico to define themselves, their culture, and their politics. Ultimately, the aesthetics embedded in the art of Jorge Soto Sánchez must be understood within this context.

First Category of Jorge Sotos Work

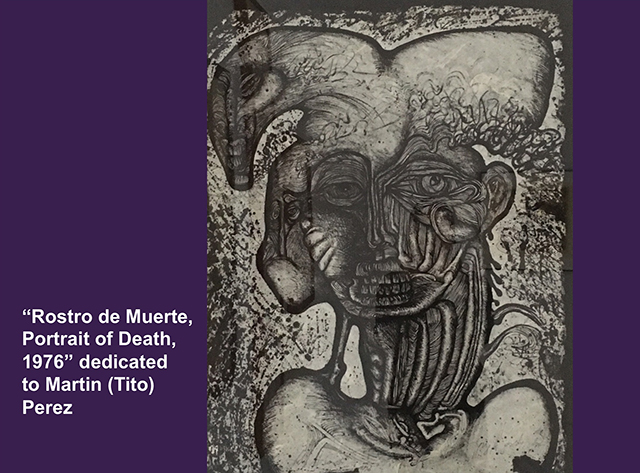

Now to the first category of Jorge Sotos work: Expressive drawings of fragmented beings using bold gestural contour lines in the graphological sentiment of his TaÃno ancestors. Let us look at the drawing entitled Rostro de Muerte, Portrait of Death, 1976 dedicated to Martin (Tito) Perez, a member of Taller Boricua who was assassinated by the Police in 1974. While many of Jorge Sotos contemporaries were using TaÃno symbols in their work, Soto used the bold gestural contour lines reminiscent of the TaÃno stone carvers and thus captured their raw graphic sentiment to create the central image of a face. The ink drawing on grey tone paper is further suggestive of stonework. Jorge then uses his expressivity by filling in the bold outline of a face with irregular patterns and spatterings of ink, suggestive of aguish and pain. He punctuates the image with a background of irregular brush strokes and again spattered and dripped ink. This is a style repeated in many of his drawings. While Jorge does not leave written documentation of the graphological influence of the TaÃno, he left multiple commentaries indicating that he looked to the TaÃno and African ancestors for his roots. I, at least, believe whether conscious or unconscious, the bold, gestural contour lines of his drawings evidences TaÃno graphology influences.

Second Category of Jorge Sotos Work

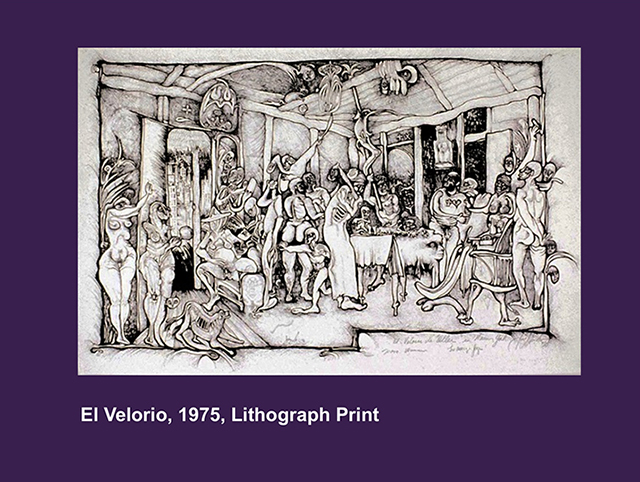

The second category of Jorges work that I would like to address is his appropriation of images from well-known Puerto Rican paintings that he transformed to express social criticism. One of the paintings that Jorge Soto appropriated was El Velorio / The Wake, 1893 by the well-known Puerto Rican artist, Francisco Manuel Oller y Cestero. This Painting shows El Baquiné, a particular ceremonial wake common in Puerto Rico at that time, which summons black angels to accompany Afro-descendant children into the next world. Ollers painting is considered one of the monuments dedicated to Negritude in Puerto Rico.

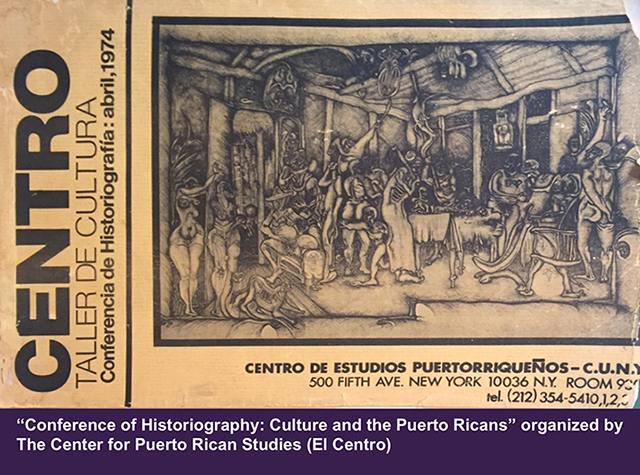

In 1974, Jorge Soto was asked to provide drawings for a publication of the Conference of Historiography: Culture and the Puerto Ricans organized by The Center for Puerto Rican Studies (El Centro). Jorge was personally impacted and concerned by the racism he experienced as a Nuyorican in the United States and Puerto Rico and decided to address this in his drawings for the publication.

Let us look at his print El Velorio, 1975, which he created after the drawings for the publication. He appropriates the familiar composition of Ollers painting. While the figures are similar in number and positioning to those used by Oller, Sotos are nude, some with exposed genitalia, some with exposed ribs, all distorted and somewhat discombobulated. There is one figure with a machete reaching towards the rafters of the room where upside down symbols and ghost like forms replace the bananas, corn, baskets, and drying meat of Ollers work. The background of Sotos piece replaces the scenic mountainside depicted by Oller with an urban landscape of sad appearing mountain-like buildings. There is a chaotic and desperate feel to the interchanges in Sotos print, as opposed to the ceremonial scene depicted by Oller. One is left wondering, perhaps with Jorge Soto, where the order and meaning has gone in this new phase of racial injustices and alienated functioning.

Third Category of Jorge Sotos Work

The third category of Sotos work I will address is his use of collected found objects and photographs, to construct painted assemblages of personal experiences representative of social conditions. His 1974 Self Portrait is a good example. He uses mostly recycled wood, probably found in abandoned buildings or sites, to create an assemblage, which he paints black. He pastes photographs on the construction outlining aspects of the figures and paints a depiction of an anguished face at the center of the piece. He then uses glazing over, ads heavy impasto lines and gestures, and drips additional painting onto the piece in an abstracted de-constructivist manner. He is now telling his story as an archetype of his generation in search of identity and meaning in an alienated environment.

At the conference in 1974 Soto stated: I was born in El Barrio; I was raised in New York and my total development took place here. I found myself isolated as a painter because I didnt feel confortable with American painters, with Spanish painters (from Spain like Goya and Picasso) and I felt very lost. And it wasnt until (I) found the taller that I felt I belonged, where I felt a connection with Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican Art.

This wonderful exhibition at Longwood Art Gallery entitled HOMENAJE: Jorge Soto Sánchez curated by Gladys Peña tells more than Jorge Sotos story. It actually tells more than the story of many of the first generation offspring of Puerto Rican immigrants from the last century. It tells the story of children of immigrants finding themselves in worlds in which they do not belong, looking back, looking at the present, and looking to the future to create meaning. It tells a story repeated again in many different ways by so many others.